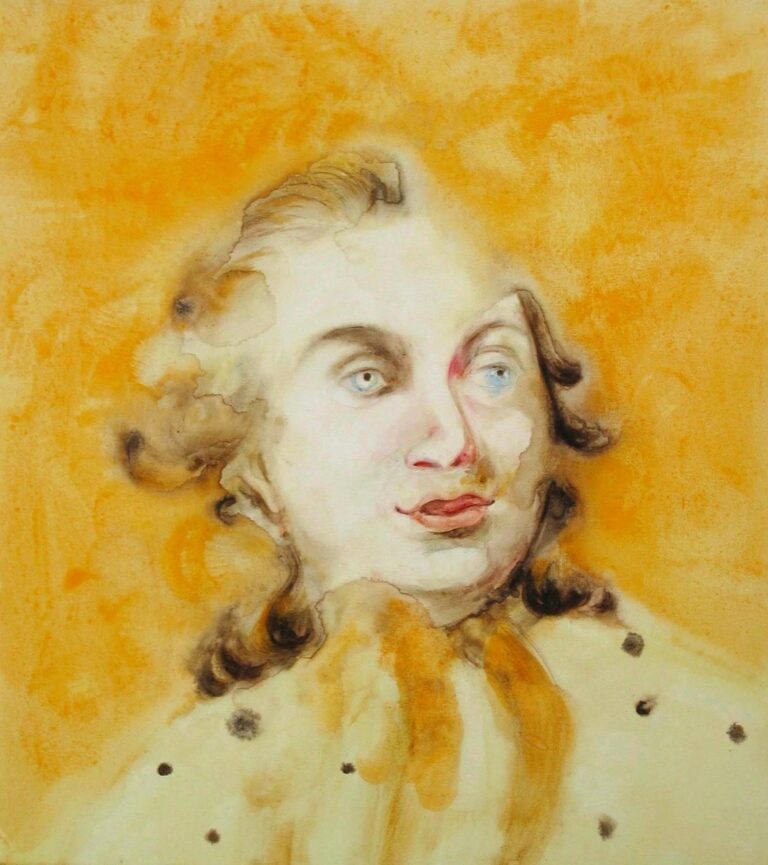

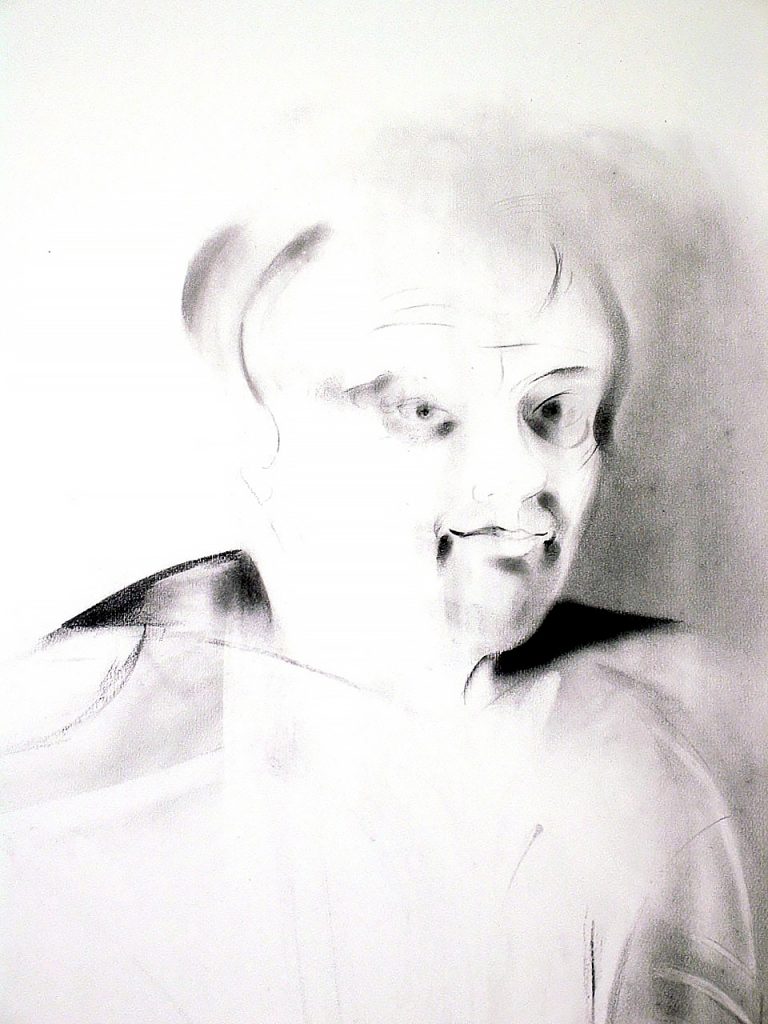

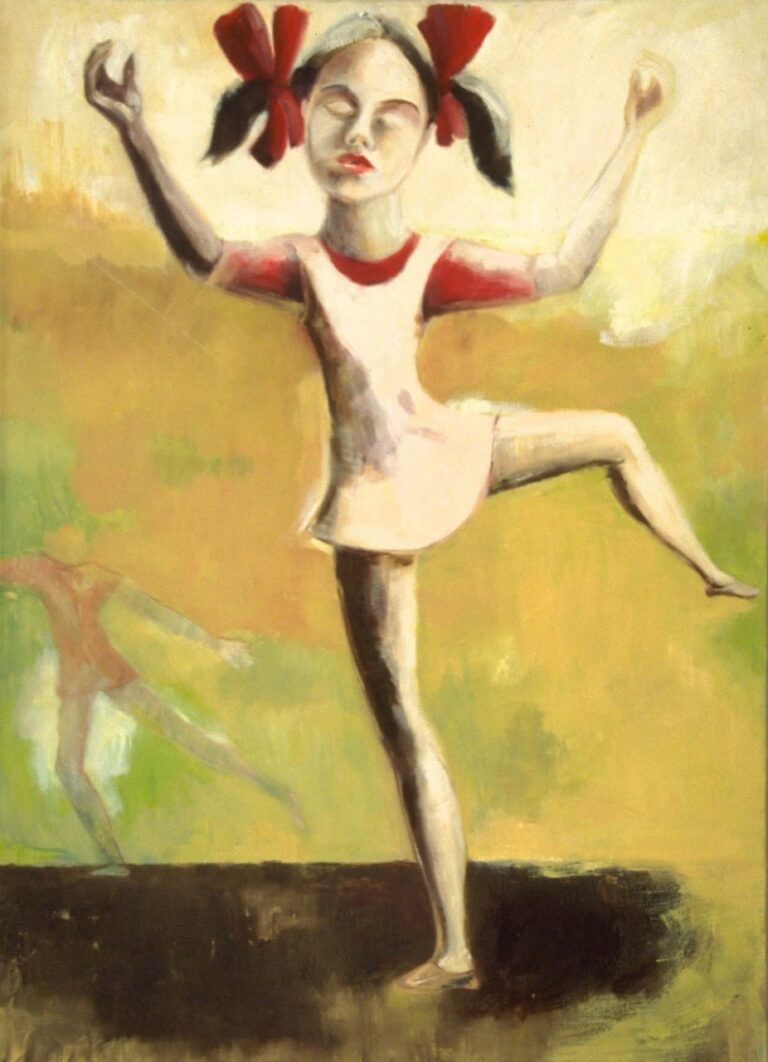

Inspired by art historical imagery, Bettina Sellmann creates what she calls “see-through versions” of Old Master paintings. Using watercolor, Sellmann soaks the canvas with pigments to build up veil-like matte layers, punctuated with a few deftly drawn lines. Her minimalist approach belies a Baroque influence, in the drenched and deep colors that accent her sinuous and scrolling forms. The overall translucency makes her subjects look ghostly and ethereal, as if they have been temporarily revived by the artist only to fade quickly back into the time period from which they came. As the colors dissolve, so does the permanence of the portrayed figure, creating a sense of isolation and inevitable decay. Although Sellmann’s subjects often refer to the seventeenth century, her process recalls the soak-stain technique of twentieth century color field painters. She also combines a contemporary technique with her historical subjects by choosing to paint exclusively from images – whether snapshots, engravings, or other paintings – while her chosen subjects evoke an intense, brooding romanticism and often refer to her favorite archetypes; kings, queens, knights, and soldiers.

Bettina Sellmann uses interesting technique to play with time and summon subjective responses to popular art and art history. Her washy watercolor-on-canvas subjects are frequently baroque and romantic; they are quaintly dated and reminiscent of kitschy things like figurines and cheap prints that, not so long ago, accented grandmother’s ersatz-Louis Quinze parlor décor.

But Sellmann’s dissolving images also have a poignant air. They gaze directly at the viewer even as they fade away. The aristocratic mademoiselle in Choker (2007) seems particularly dismayed, as if aware that, despite her finery and elaborate toilette, she has been left out in the rain. Knowing as we do what happened to French aristocrats of the Baroque era, these portraits also read clearly as memento mori. Sellmann’s playful way of exploiting a modernist technique of stained canvas, combined with her fascination of painting from well-worn images, has paradoxically given these clichéd subjects new life as ghostly presences.